← Back to Studio Visits

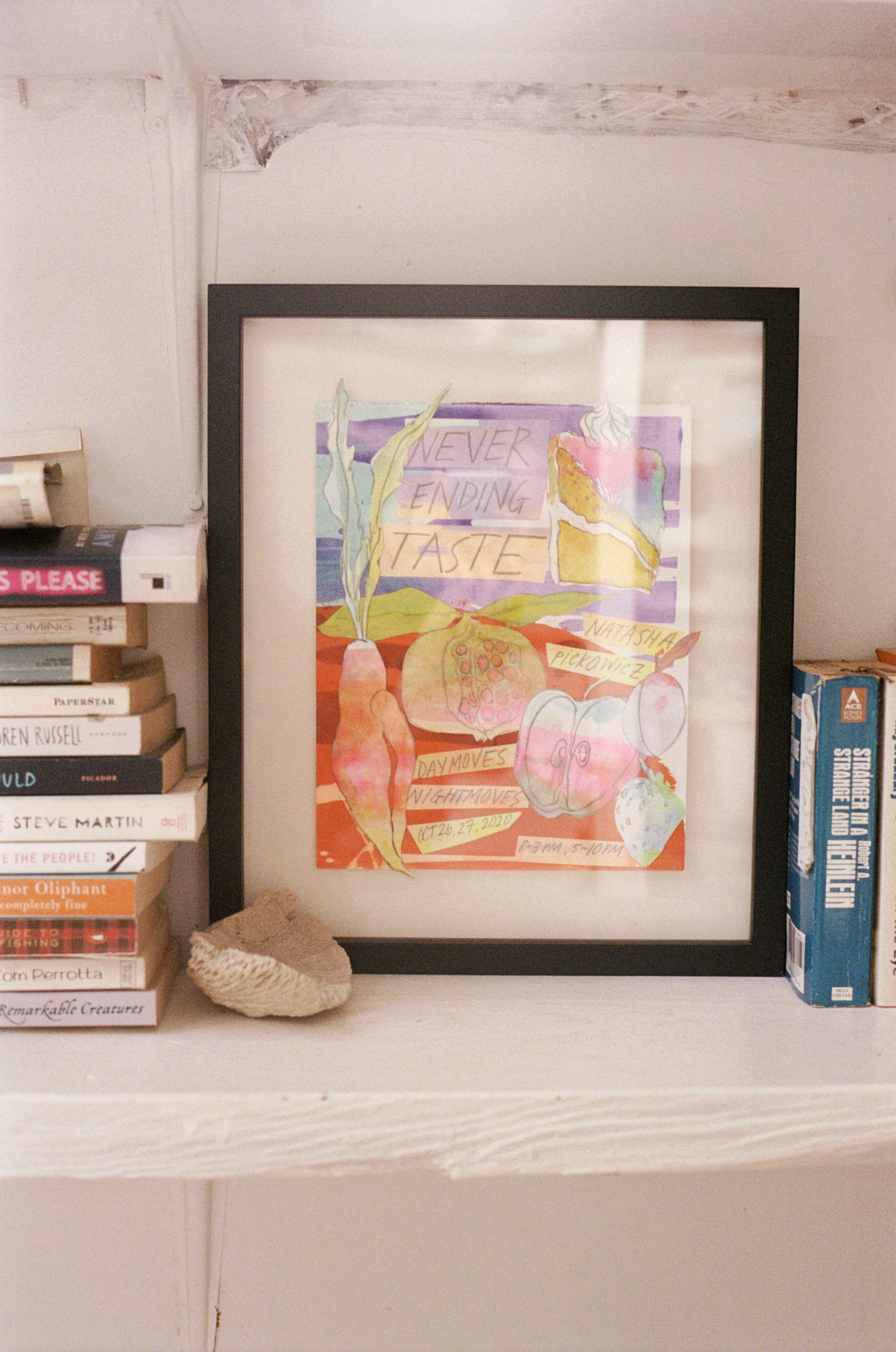

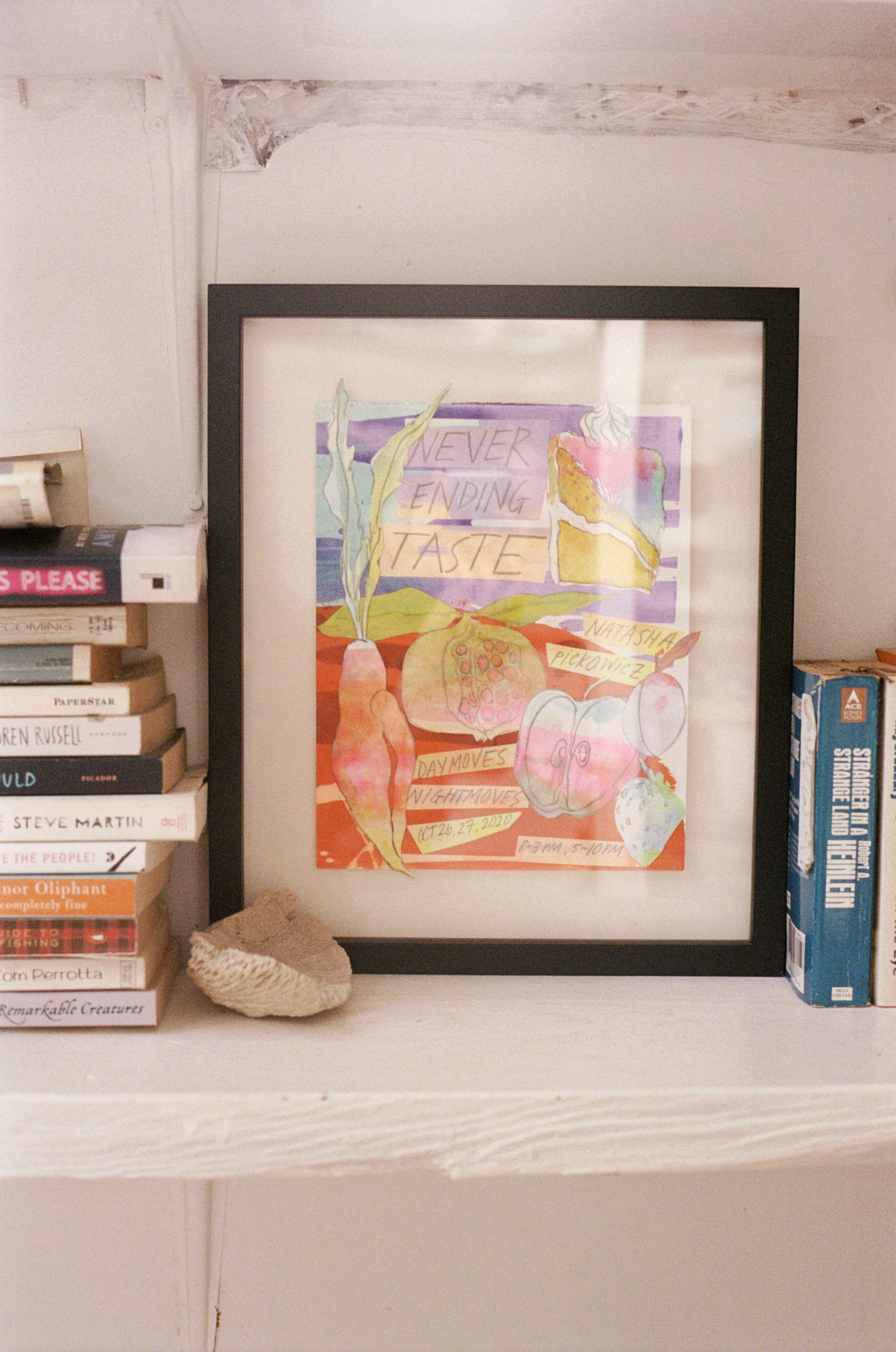

Natasha Pickowicz

Chef Natasha Pickowicz in her Greenpoint garden, August 2022.