Maggie Boyd

October 23, 2019

Maggie Boyd is very hard to take a picture of. Most of us, thanks to iPhones, have learned to stay permanently half-alert to photo opportunities. We’re semi-posed at all times, faces frozen, forever photogenic. Maggie’s fundamental lack of self-consciousness keeps her in motion. Nearly all my photographs of her are blurs: head thrown back in laughter, expression mid-transformation, body exiting the frame. Once, I got a roll of film back and the final image was a double exposure, Maggie on top of Maggie. It’s a picture of pure embodiment: two Maggie’s totally unaware, literally twice as present but actually totally absent, elsewhere, engrossed. I felt as if my camera had shoved two pictures of her together in desperation. If I fail again and again to keep Maggie’s attention when I’m taking her picture, the camera does ultimately “capture her” — any photo of Maggie shows her absorbed by the real world, oblivious to the eyes on her, telling something of her true self, that totally present person.

Maggie is a ceramicist; her work electrifies and delights. The pieces she produces en masse are the mundane made magic, sometimes manic: bowls, cups, and planters in familiar shapes painted daffy colors, drawn on, scratched out, and scribbled with. Her best-known series involves bodies: naked, female, writhing, reclining, giving birth, bleeding, being all kinds of things, none of which you typically find depicted on your coffee mug. They are called “Demoiselles d’Havingnoneofit” (a play on Picasso’s famous “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”), “Freebleeding Sur l’Herbe,” “The Birthing Demoiselles,” and “Lady Lounging on the Sea Using the Sun as Her Pillow.” They are funny and they are straightforward, in the same way that Maggie is. Her ceramic work, the small pieces and the bigger sculptures she exhibits in galleries, all seem to say, “I am here, I’m a body, aren’t you?,” a simple message that lately feels more urgent than ever.

This year, Maggie had a baby. We met right before she got pregnant, so I got to watch as she modified her studio overalls with first one safety pin, then three, to stretch over her growing bump. Tuli was born in June; he’s perfect. The birth, though, was complicated and harrowing. To detail her experience and update friends and family, she drew an annotated map of her own body postpartum. That picture was the inspiration for our interview format here, a collage of drawn self-portraits and text. I was stunned by the grace and generosity with which Maggie handled a terrifying experience. Her illustrations, both the kind she puts on her ceramics and the self-portrait she made after giving birth, are gifts that remind us all we are bodies first — that we can be truly embodied if we try and in connection to our bodies we can find freedom and a lot of fun. It’s no small thing to share so intimately and reflexively in this day and age. I’m so grateful that Maggie is here to show us how.

Georgia Hilmer: Where did you grow up? How did that place shape you?

Maggie Boyd: I grew up in Canada and I moved quite a bit between small forestry towns in British Columbia. It seems that what did a lot of the shaping was a particular shapelessness of my childhood — growing up with several different family situations and in many different homes by the time I was 16, I was never under the illusion that things had to look a particular way to fit a definition of home or family or parent, etc. I also think that growing up rurally instilled a love for nature that I didn't really understand until I moved to New York and felt a deep hunger for it.

What did your childhood look and sound and smell like?

What was the first ceramic piece you ever made?

What was your first experience with ceramics? Has it always been your primary medium?

My first clay experience was making a dinosaur in grade one or two. I remember very clearly pinching the spikes on the back between my finger and thumb and glazing the whole thing a dark forest green — even the eyeballs — and being repulsed and attracted to the shiny green orbs after they came out of the kiln. I remember thinking, "I'm better at this," when I looked around at what the other kids had made, which is an arrogant thought but I was only six so maybe that's fine.

In the first couple of years of studying art I really focused on sharpening my skills in clay and after that I moved into everything but —sound, sculpture, video, performance, installation. All usually had a clay element but I was always neglecting it to some degree because I didn't want to to commit and become what I thought was the inevitable hippie potter. I wanted to be an Artist with a capital A! So obviously the fates made me a hippie potter as punishment for my arrogance.

What was your sense of what “being an artist” meant when you were growing up? Did you have a model for that lifestyle? Where were you seeing art?

They tell me I've been drawing since I could pick up things to draw with, but my family also never really thought or spoke in terms of "art" or "artist" so much. One person I remember being called an artist was my dad's mom who painted landscapes before I was born and the other was mysterious and reclusive Uncle Bruce who lived at the top of Hospital Hill in the Tel-a-Friend Hotel. I'm pretty sure he spent a lot of his life on government assistance dealing with mental health and alcoholism and painting surreal images that no one really got to see. Once I visited him and he showed me one of his canvases inspired by de Chirico and we talked about Shakespeare and though I romanticized the experience, I rarely thought about what an artist was or what art-making was until I found out there was a thing called art school at the end of high school and applied.

When did ceramics and art-making become your full-time job? Before that shift, what other work did you do to support yourself?

I think it happened around 7 years ago now — holy crapola. Before that I had been serving in some capacity at bars, restaurants, and cafes since I was 14 years old.

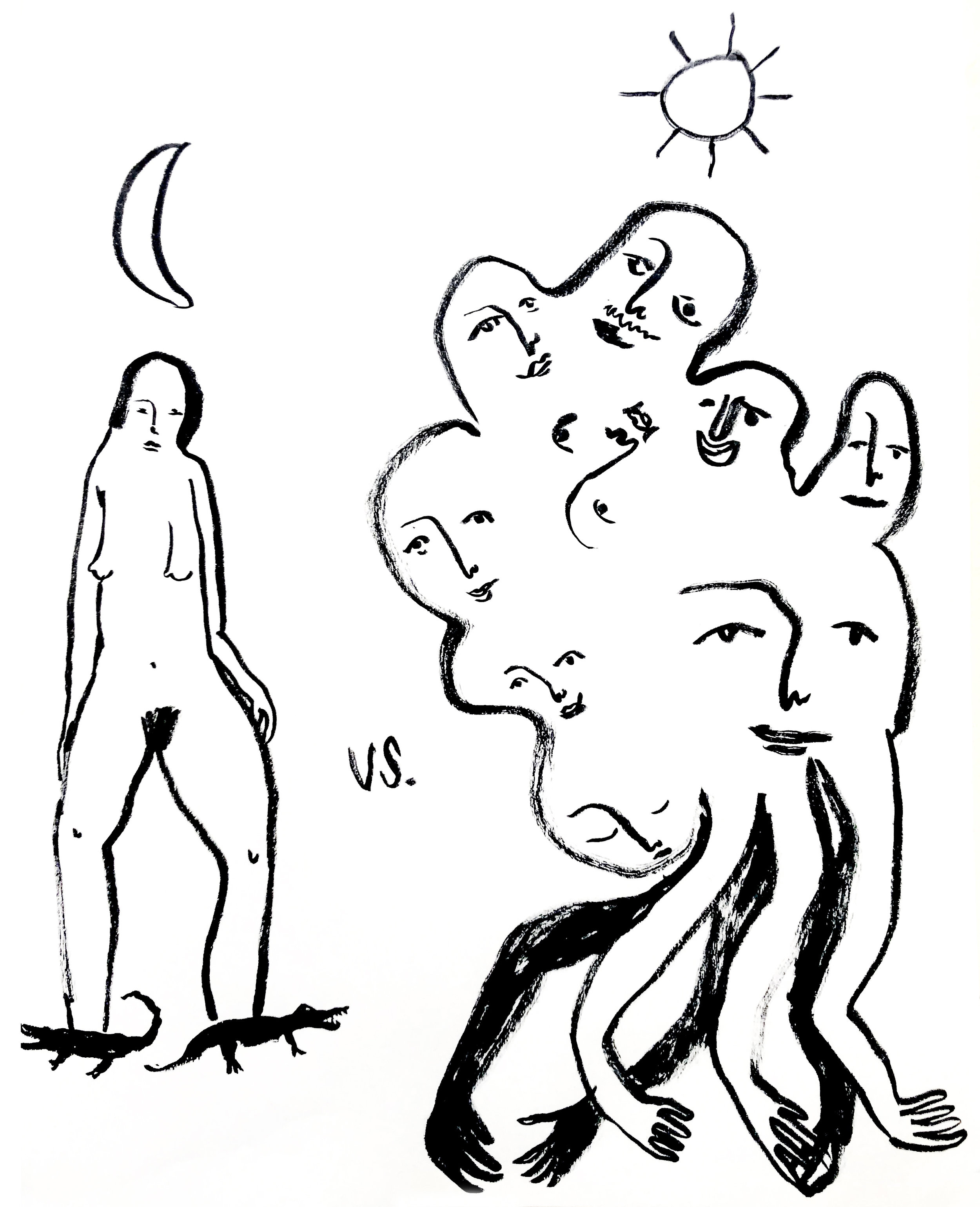

What did you think being an artist would feel like? How does it feel now? “These are the critics of the world and this is me at their feet (top). What it is actually like is more absurd (below).”

What does your studio look like when you are in the throes of creative genius?

What kind of work do you want to make in the next few years? “I want to make more big pieces like the ones I made for the Ionic Bonds show at Kamloops Art Gallery.”

“I also want to up my cups production — I want to make 1,600 of them a year. Now that I’m part of this little family with Matt and Tuli I want to set more goals like that, really crank them out in higher numbers.”

Did teaching ceramics workshops come naturally to you? Has the experience of explaining and sharing your craft with other people changed your relationship to the work

Oh man it came before I even considered myself qualified — I started teaching more than twelve years ago when I was in my early twenties — but yes, I loved teaching and even then it felt so natural. I could barely stay in school (I dropped out twice) but I was being hired to teach all these workshops and it was really confusing because I was pretty good at it and yet terrible at going to school.

What’s the balance between cup-bowl-vase-making and fine art-making? Do you distinguish between the two? When you aren’t making commissioned works for a show or throwing pieces to sell online, what does your practice look like? Is there time for play?

I guess there are pragmatic distinctions to be made between the vase that is a sculpture and the mug I reproduce for orders or sales in my online shop but in the glowing-amethyst-feeling-energy world of making in the the studio I often don't think in those terms. I know that they are all feeding into each other and can see how one thing takes me to another across the lines of production and art.

Regarding play: I think that most of what I do is routed in play or experimentation. I almost always leave a few things to experiment with in each kiln load to freak myself out with. Always chasing that glossy green eyeball repulsion/obsession feeling from grade two.

What would a self-portrait of you as a woman look like?

What did you think being an adult would feel like? How does it feel now?

What did you think New York would be like before you moved here? What is it actually like?

What would a self-portrait of you as an adult look like?

What has your recent move from Vancouver to New York revealed about your habits/desires/needs?

In this past year I have learned so much about myself and been humbled over and over and probably most importantly let some ideas go.

What would a self-portrait of you as a New Yorker look like?

“I feel like I’m starting a new stage of growth where I’m not a snail anymore. I’m creatively ambitious and ambitious in general. It feels fertile here. When I got my new studio set up here in Brooklyn, I felt like I was making some of my most favorite work I’ve made in a long time. I made some bigger pieces for shows. It’s so saturated here that it doesn’t matter what you make, I don’t think. I started to not even think about the external world or opinions and that was fun. Out of that came some more intuitive stuff. When you’re in a place where there’s so much art, you kind of can’t be wrong. When I was in Vancouver, I was more aware of myself and self-conscious. There’s an age factor too. I already went through my art school hangover and I passed through the self-consciousness that comes from imagining that you have to say something important all the time. And I experienced total ego-death when I moved here. I was thinking, “Who am I? What am I doing?” I cried a lot and then I got pregnant and everything was very high octane for a few months. When I came out of it I could start making stuff anew in a way that was really refreshing.”

What would a self-portrait of you as a Canadian look like?

“This is me as a Canadian, the snail eating a lemon. When I was living in Vancouver, I just did whatever I needed to do and nothing more. I’ve never been really ambitious, I don’t think. I feel like I moved at a slow pace and did things in my own time. I remember coming to New York for a sale once and my goal was just to sell whatever I had, shut down my table, leave the space, and not work for the rest of the month I was here. I sold out on the first night and thought, ‘Awesome, I’m done.’ Then this woman who owns a store in Soho came in and was telling me, ‘Okay, you need to get on your pre-sales and start taking orders and blah blah blah,’ she was a hustler. I thought, “Oh, I’m just totally of a different, West Coast mentality.’ So I think of myself, when I was in Canada, as a snail.”

What does a self-portrait of you as a mama look like?

What did Tuli look like when he was just born?

What did Tuli look like at two months old?

What does Tuli look like (now) at three months old?