Chioma Ebinama - Pandemic Update

September 8, 2020

Over the years, this interview project has helped me understand the myriad ways in which work defines a life, shaping it for the better and sometimes for the worse. A job can be a lifeline. It can be a dream stretched long and taut into a career. It can be a set of constraints. It can energize, demoralize, exhaust, and empower, sometimes all at once. When the coronavirus began to upend life in the United States in early March, work as we know it was disrupted. People abruptly lost their jobs, employees were told to turn their apartments into offices, and whole industries went dormant. Other previously overlooked workers became “essential,” though their low pay did not suddenly grow to reflect their new importance. In this period of crisis, I wanted to speak with some of the women featured in past Conversations to find out how the pandemic has affected their daily lives and identities.

The protests against police brutality and racial injustice that swept the US this summer also forced me to consider the ways I have failed to address race and racism both in private conversations and through this project. These updates offered a chance to ask better questions and rectify past omissions. I’m grateful for the opportunity and thankful to the women who shared their time and thoughts with me. This series has often felt like an exercise in map-making. When so many things feel uncertain, these real-time updates have helped me imagine new paths we might chart forward.

○

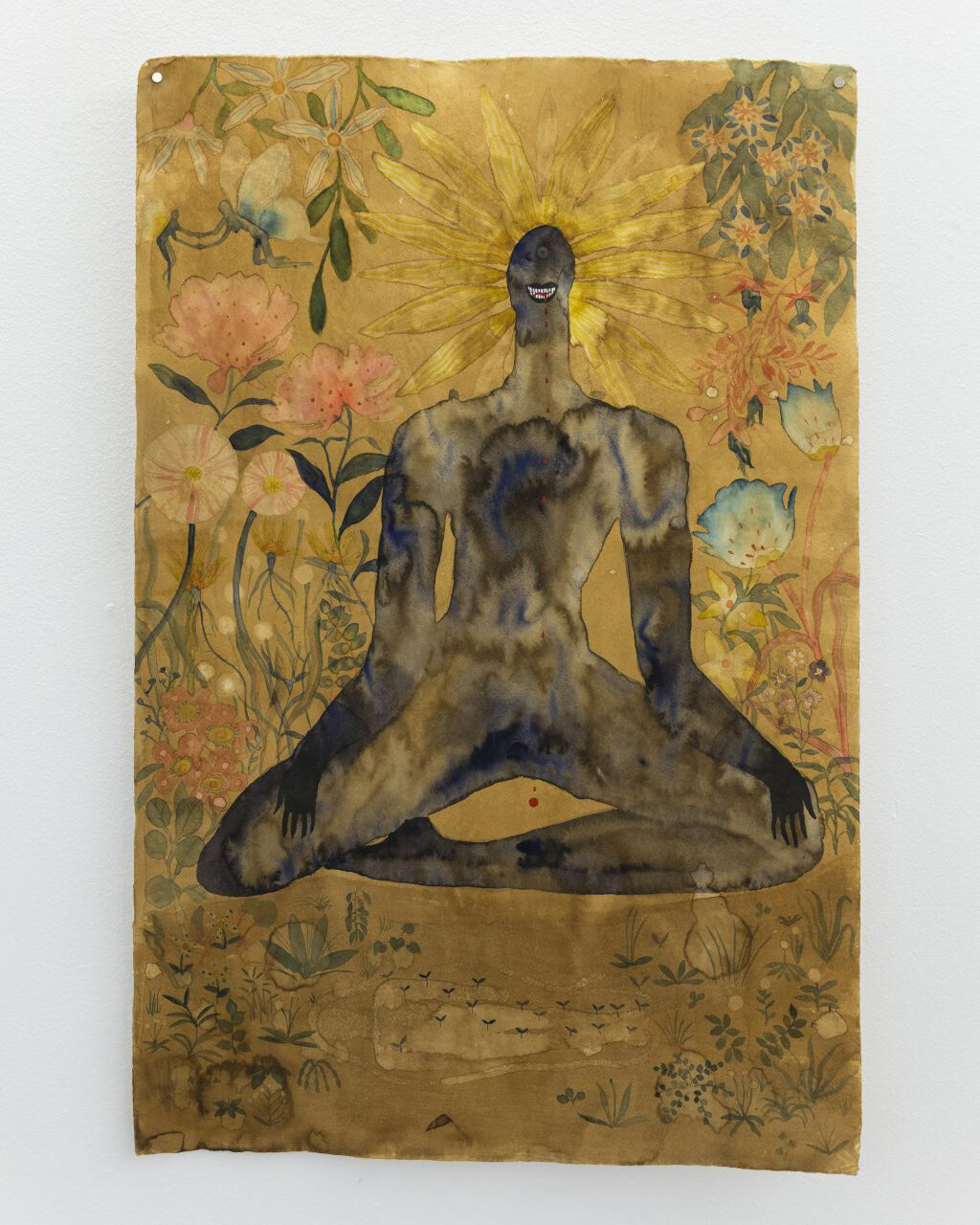

The March 2nd opening of Chioma’s solo show Now I only believe in…love was one of the last social gatherings I attended before New York City shut down and the pandemic gripped the US. That spring night seems like a dream now: so many giddy people crammed into a tiny space on East 4th street, friends standing shoulder to shoulder to peer closely at minutely detailed paintings, so much laughter and cheer. The next day Chioma left the country for what would have been a continuation of her 2019 world tour; she planned to travel to Greece and Nigeria among other places. Instead she was waylaid in Athens, where she has been living and working for the last six months. Earlier this summer The Breeder offered Chioma a show; Leave the thorns and take the rose opened September 3rd. This time, I saw the new work from my couch when Chioma streamed the event from Athens on Instagram Live. I felt continuity and disconnect at once: the work goes on but also … nothing is the same. I spoke with Chioma about what it’s like to make art during the particular crises of this moment.

This interview took place via email; it has been edited and condensed. I photographed Chioma on the roof of her apartment building in Athens over Zoom in August. The photos of Chioma’s artwork are by Lida Macha, courtesy of The Breeder, Athens.

August 2020

Georgia Hilmer: You left New York for Greece right after your show opened at Fortnight Institute on March 2nd. Soon after that the US was consumed by coronavirus. Can you explain what your travel plans were initially? How did the pandemic change those plans and how did it affect your life, both on the ground in Athens on a daily basis and emotionally, being far from family and friends?

Chioma Ebinama: By the time I left for Greece, I’d already been on a sort of world tour: Mexico, Korea, India and more. I decided to travel mostly because I was fed up with living in New York and not sure where I wanted to be. Although New York was the first place I felt really at home, it seemed as if no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t hold on to housing, I couldn’t feel fully comfortable. I was terrified to leave and didn’t really feel that I had a nomadic spirit. I feel very lucky to have had so many loving people support me through that time. As I was learning to use my wings, there were many experiences that reminded me to let go of expectations. If my other travels were practice runs, then experience of being in Athens has been the real test in learning to ride the wave. I’m hanging in there. I’m so grateful to have a space to work at The Breeder and an upcoming show in September. Lately, however, I’ve been really feeling the distance. I don’t really want to be in the States, yet at the same time the uncertainty of when I’ll be able to hug my family and friends feels quite heavy. I’m trying to sit with the reality that I can feel happy for the blessings and opportunities that have gathered around me and also grieve everything that is no longer in my grasp.

What kind of creativity did you feel after completing an entirely new body of work for your show Now I only believe in…love? Were you depleted or energized? Have you been painting and drawing much over the last few months?

I don’t believe creativity depletes. When the quarantine began my suitcase was stolen and I lost most of the materials I used to make Now I only believe in…love. So I felt I couldn’t cope with all the sudden change by just returning to that world. I started making sculptures from our recycling. It wasn’t until months later, when I finally accepted I would be here for a while, that I sought out new drawing materials. But even still, I don’t feel I am in the same space as I was for that show. Then I was eating, sleeping, and really living with that work everyday. There was little separation between my everyday life and the world I was creating. Now I’m commuting to a space every day. I forgot how much maintaining an art practice and participating in everyday life like a well-socialized human being requires building a portal you can enter and exit when needed. I’m making but also recalibrating.

We talked in late March about the tension between leading a somewhat bohemian life (your description) versus being "responsible" in this time of global upheaval. How are you thinking about your choices and obligations now? Where does the idea that art-making is indulgent come from for you personally?

First off, I’m surprised I used the word bohemian! To be honest, this dichotomy of thinking is just the internalized voice of my immigrant parents. Like most children of the immigrants in the US or even here in Europe, I am hyperaware that I don’t exist in a vacuum. Despite the individualist ideology that I’ve been fed in Western society, my actions and choices aren’t separate from my community and sharing resources isn’t just something you do when there’s a relevant hashtag, it’s part of life. I always feel a bit guilty for how much time I spend in my own world. I have to believe that I can be free but also accountable. I’ve been trying to remind myself that my ancestors couldn’t give me much in terms of material resources but through our collective struggle and sacrifice I’ve inherited time—time to think, time to create, time to heal. I’ve been in the presence of some really spectacular material wealth but really nothing is better than the luxury of time. I try to believe that it is a radical thing to fight for my time, by any means necessary.

When protests sparked in response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery at the hands of the police began to spread across the United States, what were you feeling and thinking? What effect did being farm from home have on your state of mind?

I am still wading through a lot of thoughts and feelings about this. I’ve been in Athens, Greece since before the lockdown and the same week the protests broke I was given this amazing opportunity to work on a show in The Breeder Open Studio. It has strange watching a place called home unravel while simultaneously experiencing a level of security and professional growth I had rarely experienced before. I didn’t feel hopeful that anything would suddenly change politically in the US. More than anything, I felt concerned for all of the Black people I love, especially Black women and how they would protect themselves and take care of themselves through this tense time. I felt angry that they weren’t able to share in the joy I’m experiencing, nor physically be with them through this stressful time. I think because of this, I haven't quite opened myself to being full here. My thoughts are often far away.

In our initial interview for the Conversations project, we discussed performative blackness and your experience in the US as a person who is first generation Nigerian-American, "whose sense of blackness is not rooted in the history of America" (your words). More recently you have mentioned the pressures you feel to represent yourself and your politics on social media. The recent protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism have seemed to amplify and complicate ideas of performing identity and consciousness, especially online. Can you talk a little about communicating your perspective in your art vs. on social platforms? What are you thinking as you scroll Instagram right now, where so many conversations about race and racism are taking place, blunted to a certain degree by the limitations of a square on a screen?

I’ve grown silent on Instagram and I don’t have any other social media accounts anymore. I have a complicated relationship with it because it can be a great place for sharing and learning, yet I feel sensitive to how easily it distracts me, how overwhelmingly porous I feel when I consume it. So lately I’ve just been thinking of it as a place to put my work and work-related things.

I don’t know if Instagram creates honest meaningful conversation. Is a like button part of conversing? Are people really being vulnerable or honest when their voices are mitigated by the veil of the screen? Can you fit all of an experience, a movement, or a person in a square? The primary reason I’m so wary of Instagram is that I can’t ignore how it is foremost an instrument that encourages the user to consume: consume things, consume lifestyles, consume ideas. I got so many white followers during the protests. I wondered: do they truly connect with my work or are they just eager to consume my blackness? Which I suppose is the eternal question when making anything while Black.

I know making art is what makes me feel most free and sharing and selling art affords me the time to keep making it. I wonder, however, if selling art especially through this virtual reality where my persona and my work are so fused and hyper-visible is truly in the service of liberation or just keeping me on that same old capitalist merry-go-around. Recently, I checked the hashtag for Breonna Taylor and the top posts included someone selling cupcakes, a fitness and lifestyle personality, and a photo of Black man coming off a private jet with two beautiful women, just to name a few. The other day I found an account selling George Floyd pillows. Their deaths have become commodified and it’s disturbing. When a real human life becomes a hashtag, it loses its humanity. Perhaps it is pessimistic, but I feel that until the rhetoric of pro-blackness and Black liberation are separated from capitalism, no one will ever be truly free.

Her corolla remained wide open and swollen, 2020

September 2020

I agree that fighting for your time is a radical act. Without that resource you can't take advantage of any other. How do you fight for your time? What have you learned, working as an artist, about the specific challenge of making time for yourself as a Black woman in a world that centers whiteness?

I’ve fought for my time in different ways over the years. To be honest, it took me a while to prioritize comfort and sometimes I prioritized time for making art over just living and being human. It’s best for me to think of my practice as a devotional practice, a deep love that I am returning to daily. I admit that I have always struggled to silence the voice inside that says that I am “lazy” and not doing enough. I don't think this is an internal struggle exclusive to my experience as a Black woman but I know I’ve spent my whole life watching Black women give tirelessly and work tirelessly with little in return. I’ve tried to feel less guilty about needing rest sometimes. I like to think there are generations of women in me and they’re all kind of exhausted. That said, I love a good nap and before leaving New York I used to take them regularly. That’s my favorite kind of self-care.

Can you talk a little bit about the way you have been inhabiting your studio space in Athens?

Just after the quarantine was lifted in Athens I was invited to make work at The Breeder in their project space. The space is special because it’s lived a lot of lives, at one point it was a pop-up restaurant. At another time, artists actually lived in the space (there is a kitchen and shower). This time it was set up as an open studio so interested Athenians could schedule to visit me and see what I’m working on. This took some adjustment for me. I’m used to working in total isolation either at home or not far from home. In this case, I had to be more of aware of time and when I could access the space. For the final image, Simple Plant Consciousness, I ended up taking the work home so I could have the freedom to look at it at like 2 AM. But I did learn from this experience that even if I’m not up during dream hours I can still make dreamy work. Also it was a good trial at prioritizing being human and figuring out a work and life balance that includes my partner.

Have you been able to discuss race directly with the gallery owners, patrons, and collectors you've interacted with in the art world? Have those conversations been different in the last few months?

I’ve had a few conversations but most often I try to steer conversation away from race as a “trending topic” and always bring it back to my personal experience, partly because my work is very inward and not exclusively defined by my racial category, but most importantly because I don’t feel it’s my responsibility to educate a stranger in my studio about racism. I also find that I don’t always have the patience for ignorance. This recurring tone of cluelessness irritates me. A few days before my opening, a journalist asked me to “try to help them understand the Black experience in America.” It irritated me because I think in Europe there is the notion that racism and anti-blackness is something that happens “over there.” Violence against Black people worldwide has been hyper-visible and in the public eye for a long time. Everybody who watches Black death and turns a blind eye, while also simultaneously consuming Black joy (whether art, music, sports whatever) is culpable—they are part of the problem and therefore also part of the solution. I recognize that in many cases the ignorance might be sincere but I think that the art world has a way of mystifying real world issues for the purpose of selling art. Therefore, I shine a critical eye on people that seem eager to discuss race in my studio. Perhaps I am too cynical but I can’t help but wonder if they are truly interested in me as an artist or are they seeking a piece of my blackness in a hot trending market.

How have you been staying connected to your community around the world? What are the rituals or practices that make you feel in touch with your friends and yourself?

This question reminds me that perhaps I should build some rituals or practices around staying in touch with my friends!

I have a core group of people I check in with regularly. I recently discovered that Athens has a lot of cool secondhand shops (If you don’t mind digging) and sometimes I buy clothes that aren’t necessarily my style but remind me of other people. I think I’ve been subconsciously shopping for the time when we’ll see each other again. I have a lot of clothes right now that feel very appropriate for fun times in Lagos, as if I'm sartorially preparing for my return there.

One thing I came to really appreciate from being so far from all my beloveds is that I have a lot of friends living so many different walks of life all over the globe. It has made me eager to find ways to connect all of them. How can I somehow bring all these special energies together for good? Perhaps that sort of thinking is bordering on megalomaniacal but in the midst of global transformation I think we’re all thinking about our resources. Being able to connect with all sorts of people, is a resource I had overlooked until now. I'm so grateful to have such diverse friends!